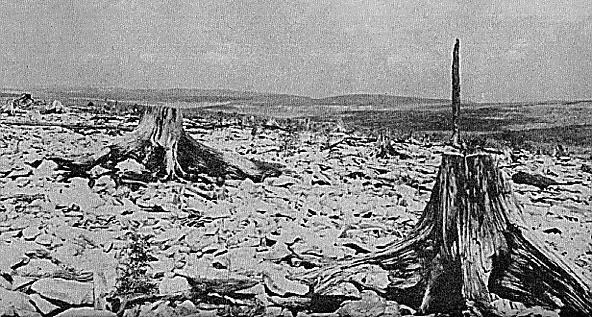

Like the barren surface of the moon, the crest of Cabin Mountain stretched out in a desolate field of rock. Cut and charred spruce stumps groped for stability appearing like petrified octopi. Botanist Harry Allard had come across this image of desolation when traversing the spruce forests of Tucker and Grant County. He walked in the wastelands following an era of intensive logging and roaring forest fires. The rocks he stepped on had once been buried by lush, wet mats while the lonely horizon had been covered by greenery just a century before. What took centuries to accumulate was gone in the blink of an eye. The life and death of West Virginia’s high altitude valleys is a story of a hidden boreal ecosystem, the transformative and self-consuming harvest of the forest, and its devastating aftermath leaving little but the seeds for rebirth.

Harry Allard's photograph of the Stony River Valley was taken in Grant County, north of Dobbin Slashings, on Cabin Mountain, via Save the Tygart

Map of the area, find the interactive version on ArcGIS

Harry Allard’s photo peers into the Stony River Valley, a section of Grant County just north of Dolly Sods and Dobbin Slashings. He described the area which stretched east to the Allegheny Front as rocky and barren. The peculiar image of isolated spruce stumps in a bare landscape merely hints at how this land once appeared. The Appalachian Forest that preceded this alien terrain was once a thriving boreal biome.

Combined USGS map of the Stony River Valley, Canaan Valley, and Dolly Sods

When the last glacial ice sheet stopped north of West Virginia, the frosty conditions encouraged cold-loving species to migrate south. As the glaciers receded and the Southern Appalachians warmed, high elevation pockets in Canaan Valley of Tucker County, the Stony River Valley, and the surrounding area remained cool and the tundra-like ecosystem persisted. A primarily spruce forest thrived, creating shaded habitat where debris and needles accumulated to form a deep forest floor. When loggers encountered the high-altitude valleys of Canaan and the Stony River, they described an all encompassing bed of humus and sphagnum moss that maintained a cool and wet blanket in the forest. It was these layers upon layers of ground cover that buried the shallow roots of spruce trees and filled in the space of the rocky surface underneath. Rhododendron thickets contributed to the shading of the understory in these climax spruce forests, while rendering travel through these “laurel hells” nearly impossible. In this environment, where a cold climate was welcomed and maintained by its inhabitants, loggers would report snow and ice persisting into the summer in some of its rocky ravines.

The logging industry was able to break into the cold and mountainous forests of Grant and Tucker Counties once the railroads pumped veins of iron through them. By 1884 the West Virginia Central and Pittsburg (WVC&P) railroad, founded by industrialist and politician Henry Davis, completed a line to the future town of Davis, WV. This line branched off the major Baltimore and Ohio railroad at the North Branch of the Potomac River in Garrett County of Maryland. In what became a speculative fervor, businessmen and speculators raced to snatch land, machinery, and enterprises whichever way they could.

In Grant County, Illinois lumberman JL Rumbarger set up shop. He established one of his mills in the town of Dobbin–which lay along the North Branch of the Potomac and on the WVC&P line in Grant County. Rumbarger had acquired land from the Baltimore financier and absentee landowner G.W. Dobbin. Eating into the forests of the Stony River Valley and south into the Red Creek watershed around Dolly Sods, Rumbarger’s enterprise boomed. By 1896 Rumbarger’s operation was considered one of the largest and most profitable businesses along the West Virginia Central and Pittsburg railroad.

The town of Dobbin, WV, via West Virginia History OnView

The Rumbarger Mill in Dobbin, via West Virginia History OnView

Company scrip from the J.L. Rumbarger Lumber Company, via WorthPoint

While Rumbarger’s enterprises began as a family operation they soon fell into the sights of bigger and wealthier competitors. Magnates like Henry Davis acquired land from the Rumbargers and capitalized on their outstanding debt to him while the Whitmer and Sons group of Pennsylvania forced a corporate takeover in 1898. By 1900 the Rumbarger mill had been joined by fourteen other sawmills that lay along the WVC&P railroad and the North Branch of the Potomac all dumping sawdust and waste into the river. Two tanneries, in Bayard and Gormania, which used hemlock and oak bark to prepare hides spewed pollutants that turned the North Branch brown.

While the forests fell and the rivers turned into sawdust-speckled slurries, Whitmer and Sons had moved operations out of Dobbin to Philadelphia, and by 1905 tycoon Robert Whitmer owned the mills all along the North Branch of the Potomac. While the Dobbin mill cut into the Stony River Valley from the north, the Babcock Lumber and Boom Company approached the region from the south, building railroads that climbed from Canaan Valley to cross Cabin Mountain.

“Loggers Stand Atop Felled Logs, Probably Dobbins, W. V.,” via West Virginia History OnView

After railroad lines were established, workers would set up temporary camps to chop trees and used teams of draft horses to drag logs to the nearest set of tracks. Once an area was depleted they packed up camp and moved on to the next patch. As land was cleared and railroads sliced through the woods, the dangers of forest fire became ever more frequent. As the shadowing overstory was cut, the thick and wet layers of moss and humus dried out under direct sunlight and became mats of flammable tinder. Sparks from railroads in addition to intentional or unintentional human causes could result in devastating forest fires.

Fires were frequent in the Dobbins area; two instances of fire caused $20,500 (over $700,000 today) worth of damage to the Rumbarger mill in 1899. One year later a fire along the WV Central Railroad line engulfed a mile of Rumbarger’s railroad in Dobbins. A fire in the Stony River Valley in 1923 stretched from Bear Rocks at Dolly Sods north for around 4.7 miles. The most disastrous instance was the Dobbin Slashings Fire of 1930. The Red Creek and Stony River watersheds lit up in flames as 24,800 acres swept the region. In some areas the forest floor burned away entirely, leaving behind only the rocks beneath and the occasional tree stump, as photographed by Henry Allard some twenty years later.

After the fires, brushes, ferns, and brakes emerged as well as fire-successive aspens, cherries, and poplars. Allard also noted some “vigorous young spruce” also dotted the Stony River Valley. Some of the work of regrowing of the forest was taken up by the Civilian Conservation Corps of the New Deal, who planted red spruce in the Dobbin Slashings area. While much of the Stony River Valley is privately owned, the Dobbin Slashings tract in Tucker County is an active project of the Nature Conservancy, aiming to protect the frost-pocket wetland and watershed it contains. The Dobbin Slashings Preserve was opened to the public in June of 2025, covering 1,393 acres. While the environment that has regenerated is markedly different than what preceded it, lacking the centuries that created features like thick moss-soil beds and mature old-growth trees, a new ethic of land management brings hope for the next generation of life in the Appalachian Forest.

References

Allard, H.A. and E. C. Leonard. “The Canaan and the Stony River Valleys of West Virginia, Their Former Magnificent Spruce Forests, Their Vegetation and Floristics Today.” Castanea 17, no. 1(1952): 1-60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4031603.

American Lumbermen. Vol. 2, Chicago, IL: The American Lumberman, 1905.

“Ax and Saw Are Active.” Parsons City Advocate, 30 Jun 1899, 2. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn86092348/1899-06-30/ed-1/?sp=2&st=image.

Clarkson, Roy. Tumult on the Mountain: Lumbering in West Virginia 1770-1920. Parsons, WV: McClain Printing Company, 1964.

“Disastrous Fire at Dobbin.” The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, 15 Sep 1899, 1. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn84026844/1899-09-15/ed-1/?sp=1&st=image.

“Dobbin.” The Pocahontas Times, 22 July 1915, 1. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83004262/1915-07-22/ed-1/?sp=1&st=image.

“Local and Otherwise.” Parsons City Advocate, 25 Aug 1899, 3. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn86092348/1899-08-25/ed-1/?sp=3&st=image.

“Local and Otherwise.” Parsons City Advocate, 4 May 1900, 3. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn86092348/1900-05-04/ed-1/?sp=3&st=image.

Rasmussen, Barbara. Absentee Landowning and Exploitation in West Virginia, 1760-1920. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1994.

Schaeffer, A.J. “History of a Week.” Marshall County Democrat, vol. 49, no. 6, 22 Oct 1896. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=MCD18961022-01.1.2&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN----------.

Smith, John W. Maryland Geological Survey: Allegany County, Baltimore, MD: 1900.

“Solitude and human history intertwine in the Dolly Sods Wilderness.” Sierra, 1 Sept 2001. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2001-5-september-october/field-trip/solitude-and-human-history-intertwine-dolly-sods.

West Virginia Highlands Conservancy. “The Dolly Sods Area–32,000 Acres in and adjacent to the Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia.” July 1971, https://wvhighlands.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Dolly.Sods_.Wilderness.prop-trail-guide.1971.H.McGinnis.pdf.