By David Abruzzi

Founder, Cacapon Preservation Solutions, LLC

The earliest commercial tanneries in the United States began operating around 1790 along the Hudson River on the southern tip of Manhattan. The area gained the moniker “the Swamp” because of the tanning’s byproducts of noxious odors and waste.

The tanneries mostly processed hides shipped to New York by sea from the West Indies and Central and South America. The tanneries used primarily oak bark since forests of oak were plentiful in the area; however, the growth in the city’s population and the deforestation of the nearby oak forests coincided with the discovery in the UK in 1805 that hemlock bark could be readily substituted for oak bark in the tanning process. The slopes of the Catskills were covered in millions of hemlock trees and the Catskills also offered plentiful water for the tanning process and the navigable Hudson for shipping finished hides to market leading tanneries to move upriver.

The Tannery in 1950

The first tannery opened in the Catskills in 1817 with the industry peaking in the area less than 30 years later. At its peak 64 tanneries operated in the region and used up 70 million hemlock trees in their tanning process. The rapid deforestation of the Catskills required tanneries to go farther and farther out to gather the necessary tanbark for tanning. That deforestation, coupled with the growth of railroads in the 1850s and 1860s, led major tannery companies still headquartered in New York City to seek out more financially advantageous locations. The consolidation of individual stockyards outside Chicago into the Union Stock Yards in 1865 offered a more readily available source of cowhides over sources that had been shipped from overseas locations. These changes made WV an ideal place to open new tanneries.

West Virginia after the Civil War was perfectly situated to become a center of the tanning industry. The state offered vast tracts of tanbark forests, plentiful water, and several navigable rivers, and rail. The B&O railroad offered a connection from the Midwest to Baltimore and its port as well as connections to rail lines up and down the east coast and large population and industrial centers like Philadelphia, New York, and Boston.

West Virginia’s mountainous landscape limited industrial development and the terrain also could not readily support large agriculture operations. These factors left a large segment of the population seeking steady work which the labor-intensive tannery industry offered. Tanneries provided consistent work, and much-needed seasonal income to the farmers who peeled bark from trees in their woodlands. The tanneries also spurred small family-owned businesses to open to provide goods for tannery workers who often lived far from any other stores or commercial entities.

While New York tanneries did not begin relocating in earnest to West Virginia until after the Civil War, one of the earliest commercial tanneries established in West Virginia was The Centre Wheeling Tannery founded in 1849. The tannery’s location was strategic given the city of Wheeling was the terminus of both the B&O Railroad and Pennsylvania Railroad Systems on the east side of the Ohio River. The B&O had reached Wheeling in 1852 and the city of Chicago in 1874.

Originally located on the island, the tannery began with just 10 vats in 1849, but by 1852 had grown to need 78 vats to meet the demand for their tanned leather. A flood in 1852 wiped out the tannery but it was rebuilt. Between devastating floods, fires, or both, most WV tanneries were rebuilt during the course of their operations.

In 1889 the J. G. Hoffmann & Sons company, the owners of The Centre Wheeling Tannery, purchased the existing tannery in Gormania, WV and operated it until 1925. The acquisition and consolidation of tanneries played out across West Virginia through the late 1800s and into the early 1900s.

The United States Leather Company (often during its time called the “Leather Combine” or “Leather Trust”) was established as the largest leather company in the United States in 1893. The company operated as a cartel created by the owners of 200 tanneries who combined their holdings into one entity to seek better prices from the Union Stock Yards by “cornering” the market on cow hides. The company was also concerned with access to a steady supply of tanbark. Through their combine the company obtained ownership/access to 75% of the bark property. Throughout its history the United States Leather Company operated under various names and subsidiaries and had several tanneries in WV with the largest being at Paw Paw. During the company’s existence they owned and operated tanneries in New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and as far west as Wisconsin.

The company was one of the original 12 companies listed on the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1896 and has the unfortunate distinction of being the first and only original company to have completely disappeared. It was initially capitalized (valued) at $130M which would equate to $4.6 billion in 2025 dollars.

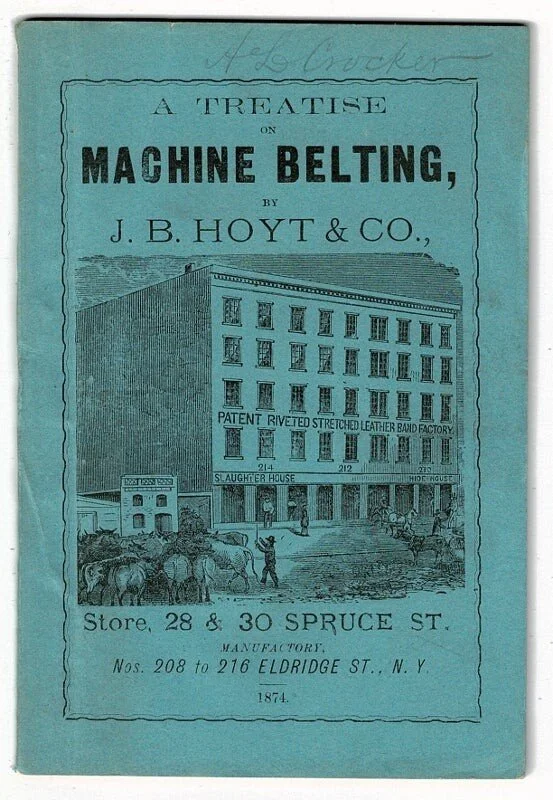

In 1868 the Hoyt Brothers from New York opened a tannery in Paw Paw and in 1870 the firm of J. B. Hoyt & Company was formed which became a holding of the United States Leather Company in 1893. The Paw Paw location was likely selected because of its location on a large flat parcel of land on the banks of the Potomac River adjacent to the B&O Railroad mainline and the C&O Canal directly across the river. The location also provided access to an abundance of oak forests on both sides of the Potomac River for tan bark.

The owners of the Paw Paw Tannery were quite civic minded. J.J. Hetzel, who had joined the J.B. Hoyt & Company in 1875 as an auditor and eventually rose to the position of general manager of their 14 tanneries, was elected to the WV House of Delegates to represent Morgan County in 1882. In 1875 the tannery donated funds to construct the St Charles Catholic Mission Church on the outskirts of the village. In 1870 the tannery had even built a school on tannery property since no public school existed. After a public school was constructed for white students the tannery offered the schoolhouse for use to educate black students under West Virginia’s “separate but equal” education system.

By 1885 the Paw Paw Tannery employed 100 men and by 1887 the labor force at the Tannery had grown to 180. With the growth of the tannery the local community was also growing and reached 1,000 (20% of the county’s population) in 1887.

In the spring of 1930 a fire struck the tannery. The May 2, 1930 edition of the Mineral Daily News & Keyser Tribune reported a catastrophic fire had occurred at the Union Tannery complex in Paw Paw. The fire destroyed two the five units at the plant, caused an estimated $100,000 ($1.9M in 2024 dollars) in damage, and resulted in 150 men being laid off while the units were rebuilt – devasting for the town of 800 as the Tannery was the town’s primary employer.

In 1930 radio personality Lowell Thomas presented“17 Years Under the Sea” on his radio broadcast. The story was about the recovery of cargo from a ship sunk carrying belt leather from the Paw Paw Tannery 17 years earlier. The leather was reported to be still as supple and fine as the day it left the tannery despite being exposed to seawater for all those years.

By the 1930’s it was said the tannery was producing more than 500 hides daily and employed more than 200 men. This made it the largest producer of industrial belt leather in the world.

The Tannery during the 1936 Flood

Another disaster hit the tannery and the town of Paw Paw in 1936 as the St. Patrick’s Day flood inundated low lying areas along the Potomac River. At Paw Paw the Potomac River crested at 54 feet which was 26’ above normal flood stage. The tannery and the town again rebuilt.

In 1939 United States Leather moved a stamping operation from New Jersey to establish a Cut sole shoe factory in Paw Paw. With that came additional employment and by 1940 the population for Paw Paw had grown from less than 800 in 1930 to more than 1000 in 1940. The tannery now employed 450 workers. Local historian Jeanne Mozier reported that women were hired to fill vacancies in the tannery caused by men going off to war. Despite the tannery’s success in the early years of the tannery’s operation the Morgan Messenger often published reports about periodic idling of tannery operations due to a lack of market for their products. In such cases men were sent home for a few days or often longer without pay while the tannery waited for demand to pick back up.

While the 1940’s were a period of prosperity it was relatively short-lived as the tannery shut down its operations in December 1951. The shutdown is attributed by some to be the result of a decision by local workers to unionize; however, it was likely a multitude of factors. West Virginia tanneries began to disappear in the 20th century as deforestation depleted local tanbark supplies. Demand for harness leather diminished as automobiles took over the roads, large belt-driven factory equipment was being replaced with more modern machines negating the need for industrial belt leather, and synthetics, such as synthetic rubber, cut into the market for sole leather.

Following the tannery’s closure the property was sold to Walter Brock of Cumberland, MD and from 1957 to 1961 Avon products leased space. In 1970 Vesuvius Crucible from Swiss Vale, PA purchased the property and used a portion of it for warehousing and shipping. In 1975 the company began manufacturing graphite refractories before eventually shuttering the plant.

The last major vestige of the plant left standing was the water tower that remained as an iconic landmark until it too was demolished on October 1st, 2011.

In the story of Paw Paw and its tannery we see an outside company coming in and setting up shop to take advantage of/exploit WV resources. While the tannery did do civic good and provided reasonably steady employment tanneries extracted an enormous amount of resources to make their product. Oftentimes tanneries held back other commercial ventures due to the stench from the tannery process and the harmful effluent released into rivers and streams. Given the change to synthetics, and the move towards motorized transportation, there was no real way the tan bark tanneries could compete or pivot to address the changes.

Today the Town of Paw Paw seeks to pivot to a tourism facing focus and take advantage of its location less than a mile from the Paw Paw Tunnel. Twenty thousand to 30,000 visitors come to the tunnel each year by car and several hundred thousand more pass by as through riders on the C&O canal. Paw Paw is ideally located midway between Cumberland and Hancock Maryland (roughly 30 miles from each) making it the perfect place to stop and spend the night. The town has a Bed & Breakfast, a hostel, glamping cabins, and an Air BnB to serve bikers and visitors seeking a comfortable place to spend the night.

Work is also underway to develop and market gravel trail biking routes with Paw Paw being the jumping off point for a number of routes for bikers of all ages and skill levels. Canoeing on the Potomac, hiking in Greenridge Forest, and kayaking and floating on the Cacapon River are also options.

Paw Paw is a member of the C&O CanalTowns Partnership and has a seat on the county CVB ( Travel Berkeley Springs) which is marketing an “Over the Mountain Campaign” to draw visitors from Berkeley Springs over the mountain and through western Morgan County to experience what it has to offer in the way of history, outdoor recreation, and hospitality.

*Note: This essay is an excerpt from a presentation given at the September 2025 AFNHA Summit.