Plants and People

Our 2022 season exhibit, Plants and People, explored wild plant traditions in the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area. Even just two hundred years ago, the hills of Appalachia were covered by deep mountain forest, which at the time seemed inexhaustible. The people who lived here were dependent on the plants found within it for food, medicine, and material. Botanical knowledge was passed down through generations and across communities, creating a culture and traditions intertwined with the landscape that endure today.

See the full exhibit panels here and photos of the exhibit here.

Plant Traditions

People have been living in the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area for at least the last 12,000 years. Native American Nations with ancestral ties to the region include the Lenape (Delaware), Seneca, and Shawnee. Having lived closely connected to the land for generations, these peoples held vast knowledge of the plants and animals of the Appalachian forest.

Virgin timber forest

Image courtesy of USDA Forest Service

In the mid 1700s, European settlers like the German, Scots-Irish, and English began to arrive, as well as African Americans—some free, but many enslaved. They brought familiar plants and seeds with them from Europe and Africa. Most of the flora found in the Appalachian forest was unknown to them however, so they relied on the knowledge held by the Native Americans to learn which plants could be used, and how. Since travel across the mountains was difficult, farms and settlements were relatively isolated and people relied on their botanical knowledge to be self-sufficient.

When illness arose, many communities had a healer who was especially knowledgable about herbal remedies whom people could go to to be cured. For more about healing traditions in the Appalachians, see the full exhibit panels.

A Year in Appalachia, Through Plants

Spring

Creasy Greens (possibly Barbarea verna)

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Coal River Folklife Project Collection

The first greens to push their way through the soil in the spring were a welcome sight. Plants like sassafras, ramps, creasy greens, and wild strawberries were known as spring tonics, and were some of the first fresh foods that could be enjoyed after a winter of eating preserved meat, beans, and potatoes. These plants provided important nutrients and minerals, and were thought to purify the blood and boost immunity after the long, slow winter months.

Ramp Suppers Nothing signals the coming of spring quite like the potently-scented ramp (Allium tricoccum). For generations, Appalachians have headed up to the mountains with family and friends to forage for the wild onion. Communities celebrate the ramp harvest in late April with dinners and festivals across the state.

Cleaning ramps in preparation for a ramp supper. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Coal River Folklife Project Collection

Sassafras branch (Sassafras albidum)

Image courtesy of the Missouri Department of Conservation

Sassafras tea is a traditional spring tonic, brewed from the tree’s roots. The Cherokee would also chew the roots to remove the odor from eating ramps! Lenni Lenape elder Gladys Tantaquidgeon used young sassafras shoots to make an eyewash, a treatment passed to settlers and employed for over two hundred years.

Summer

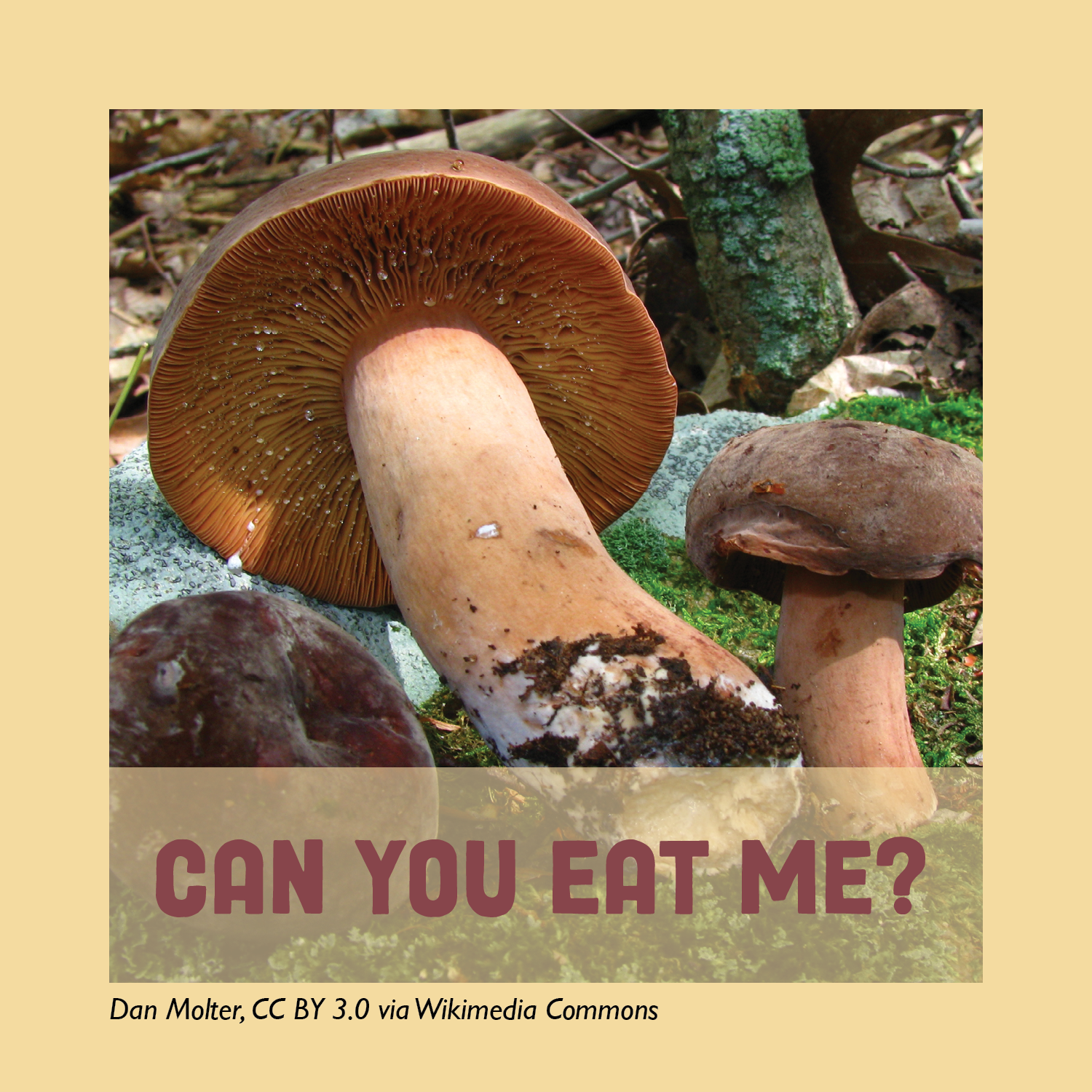

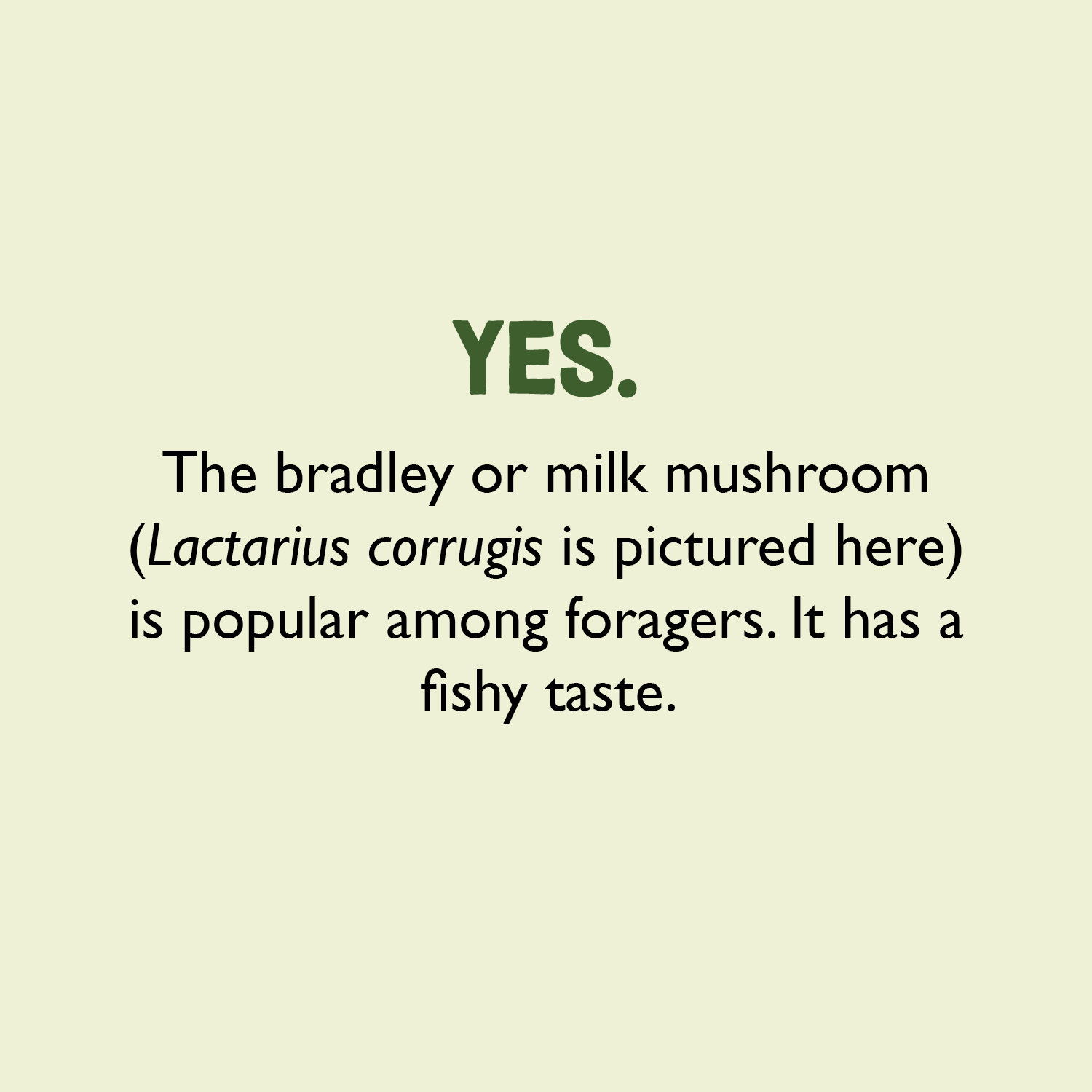

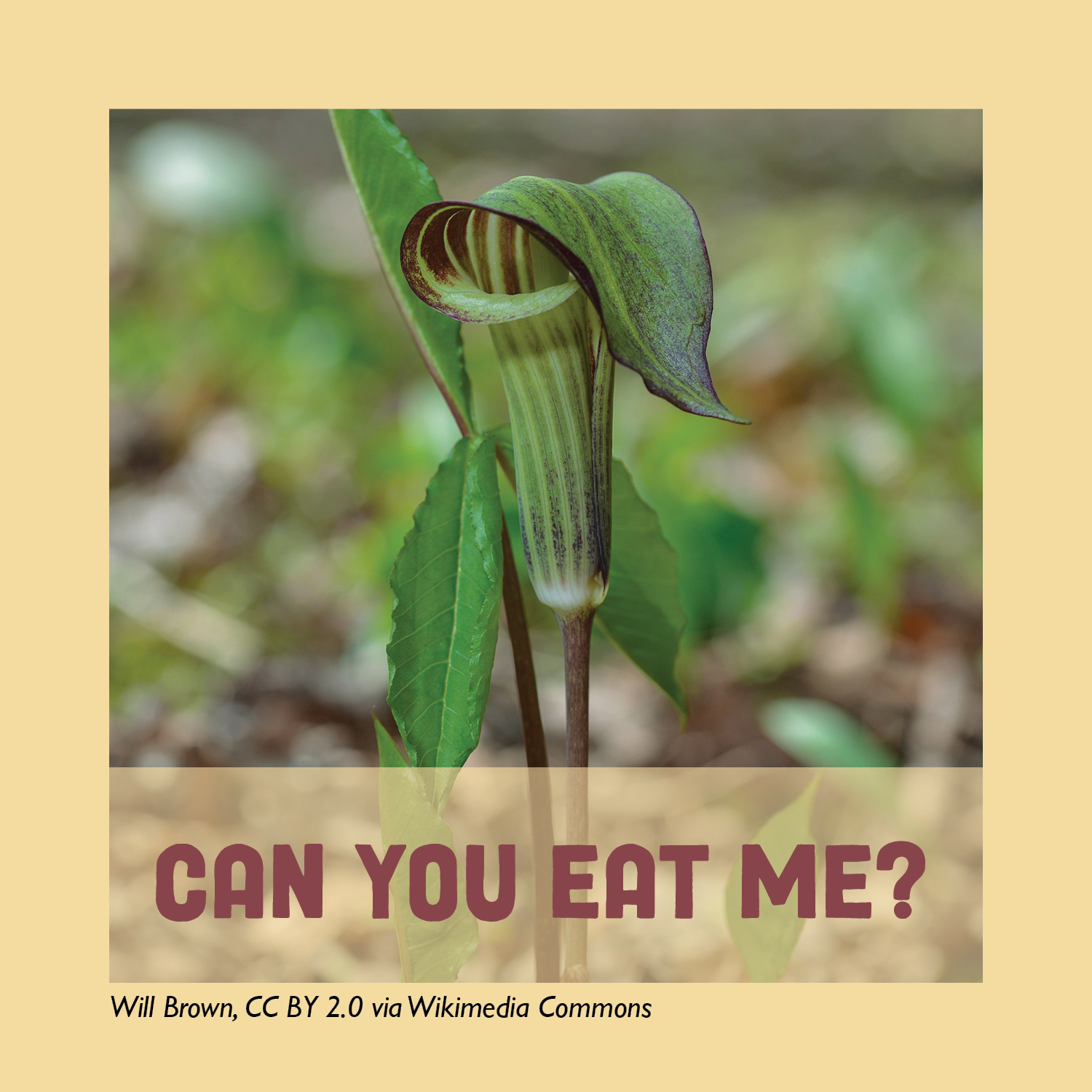

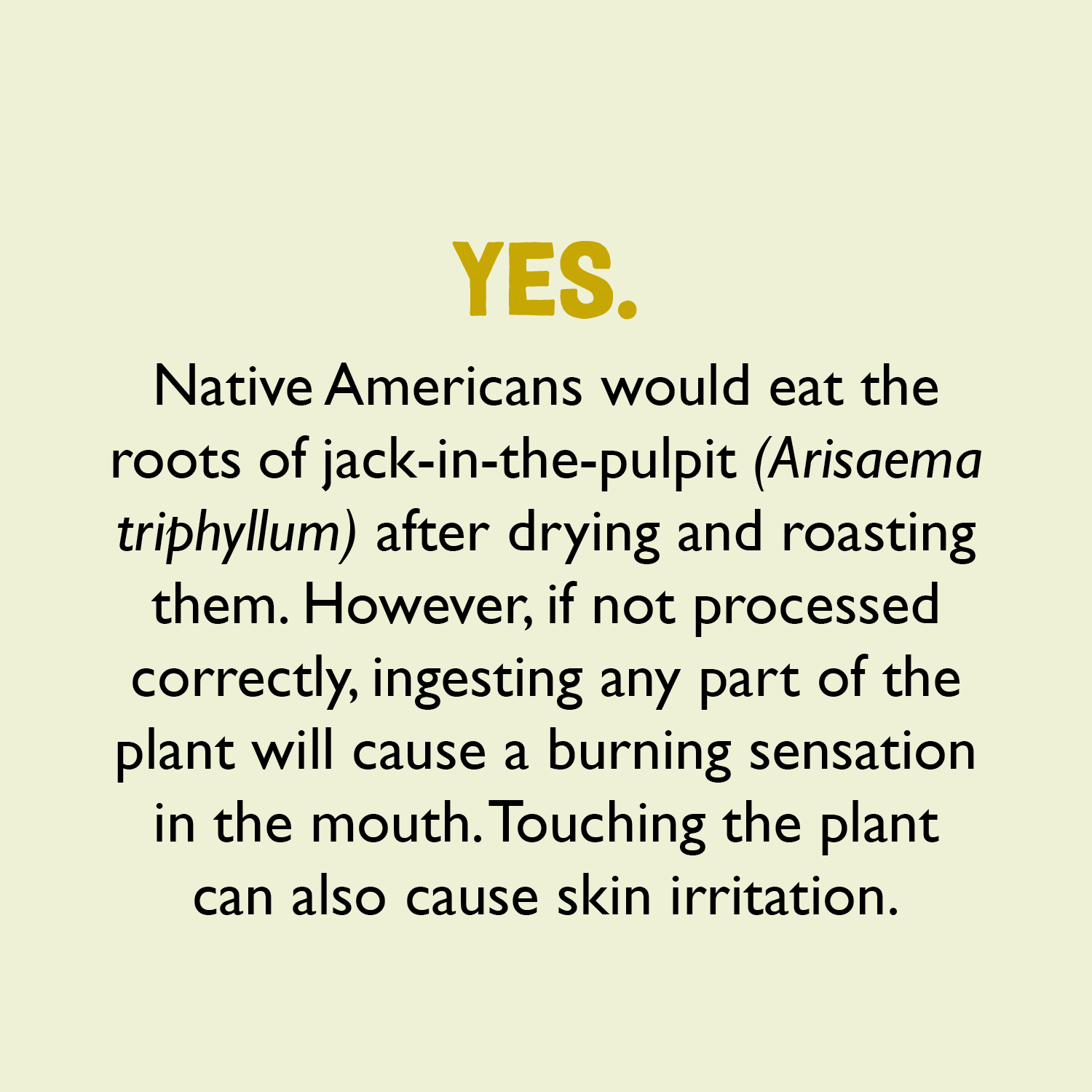

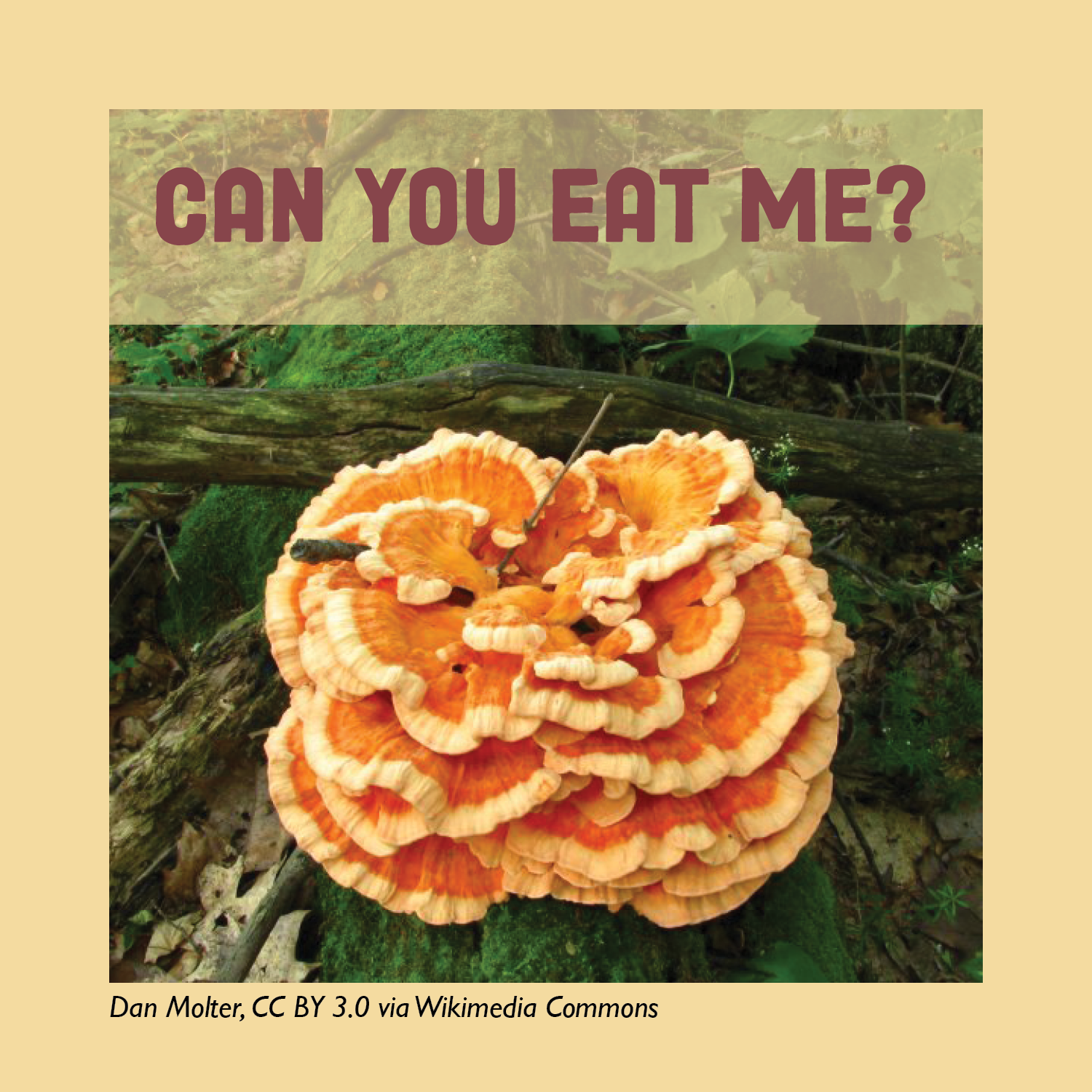

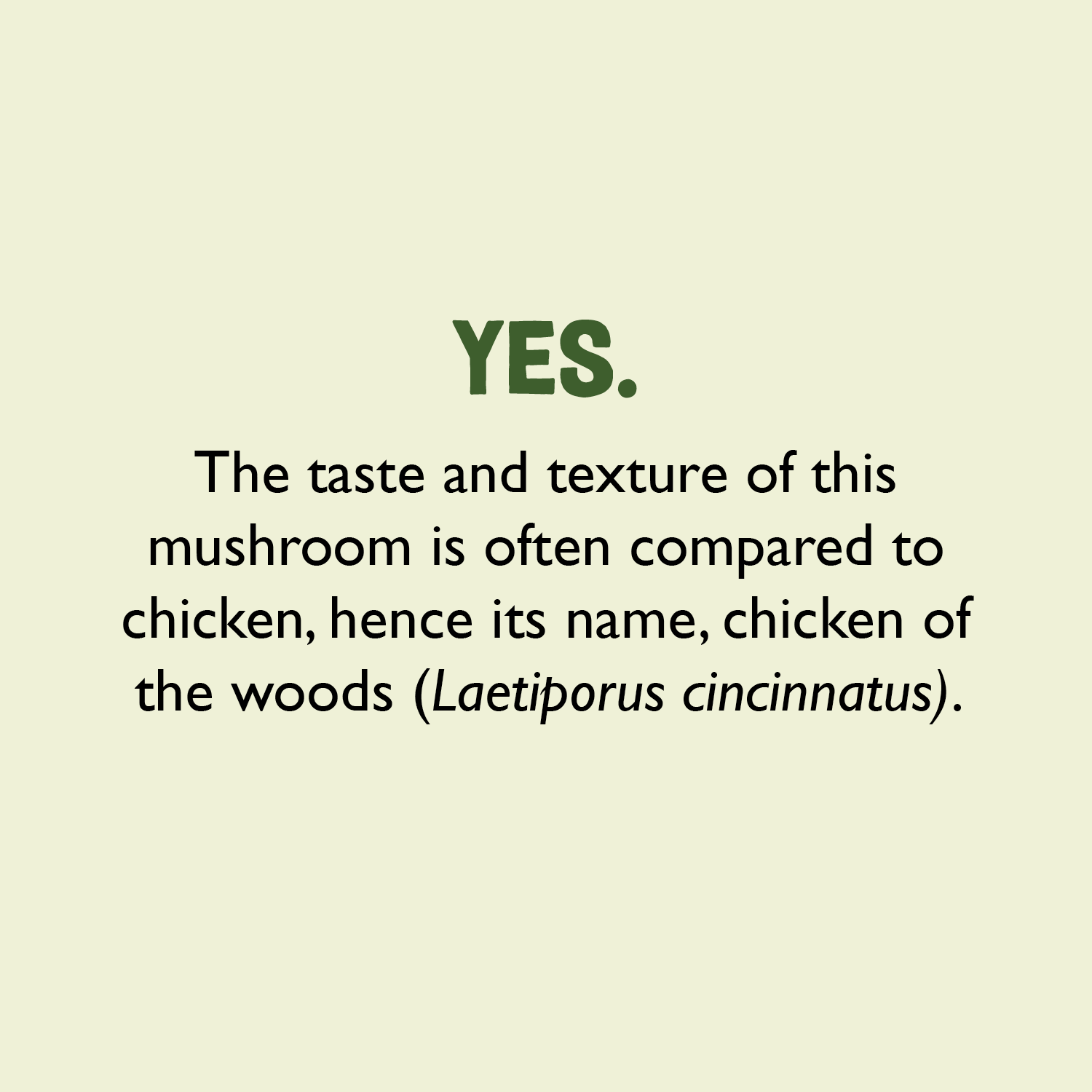

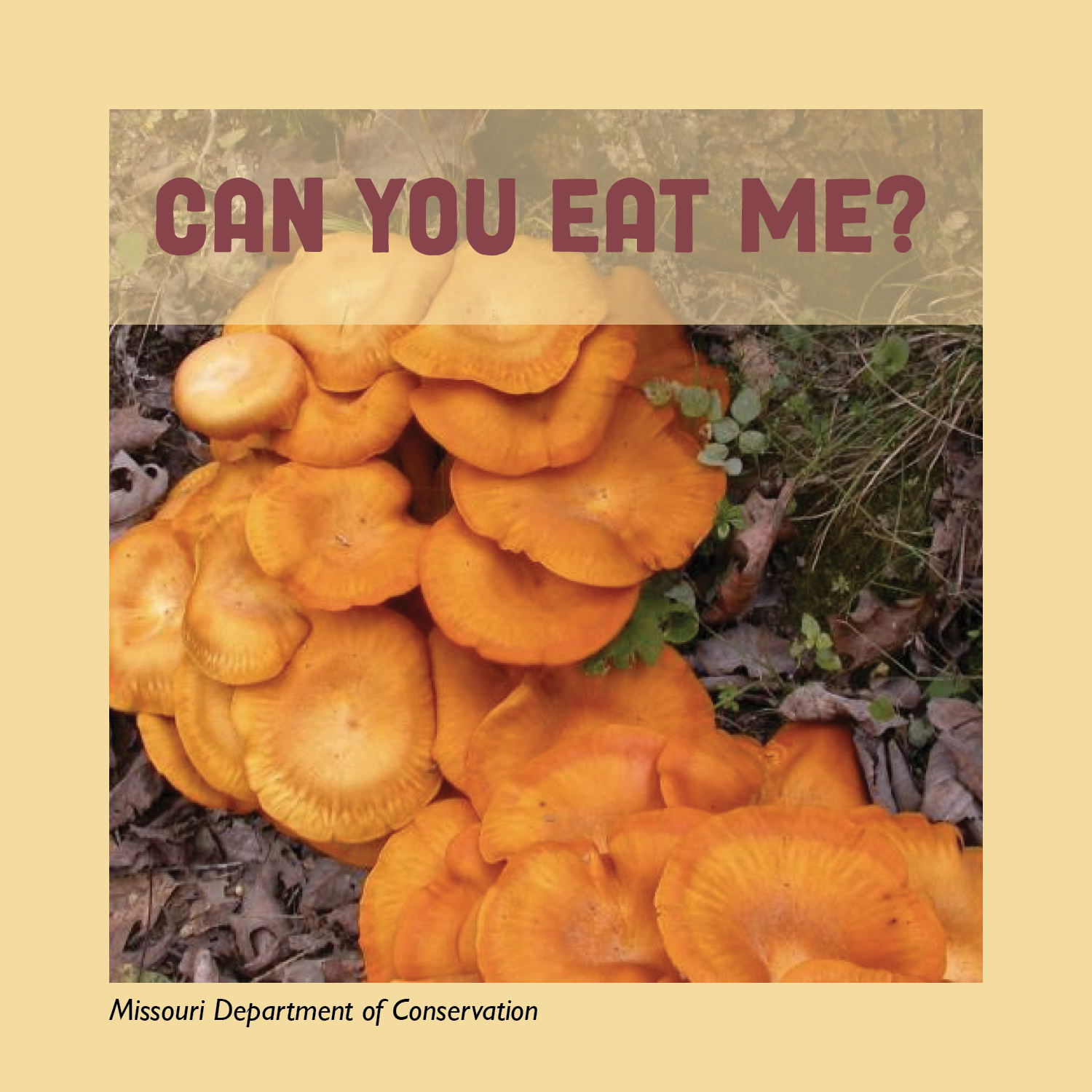

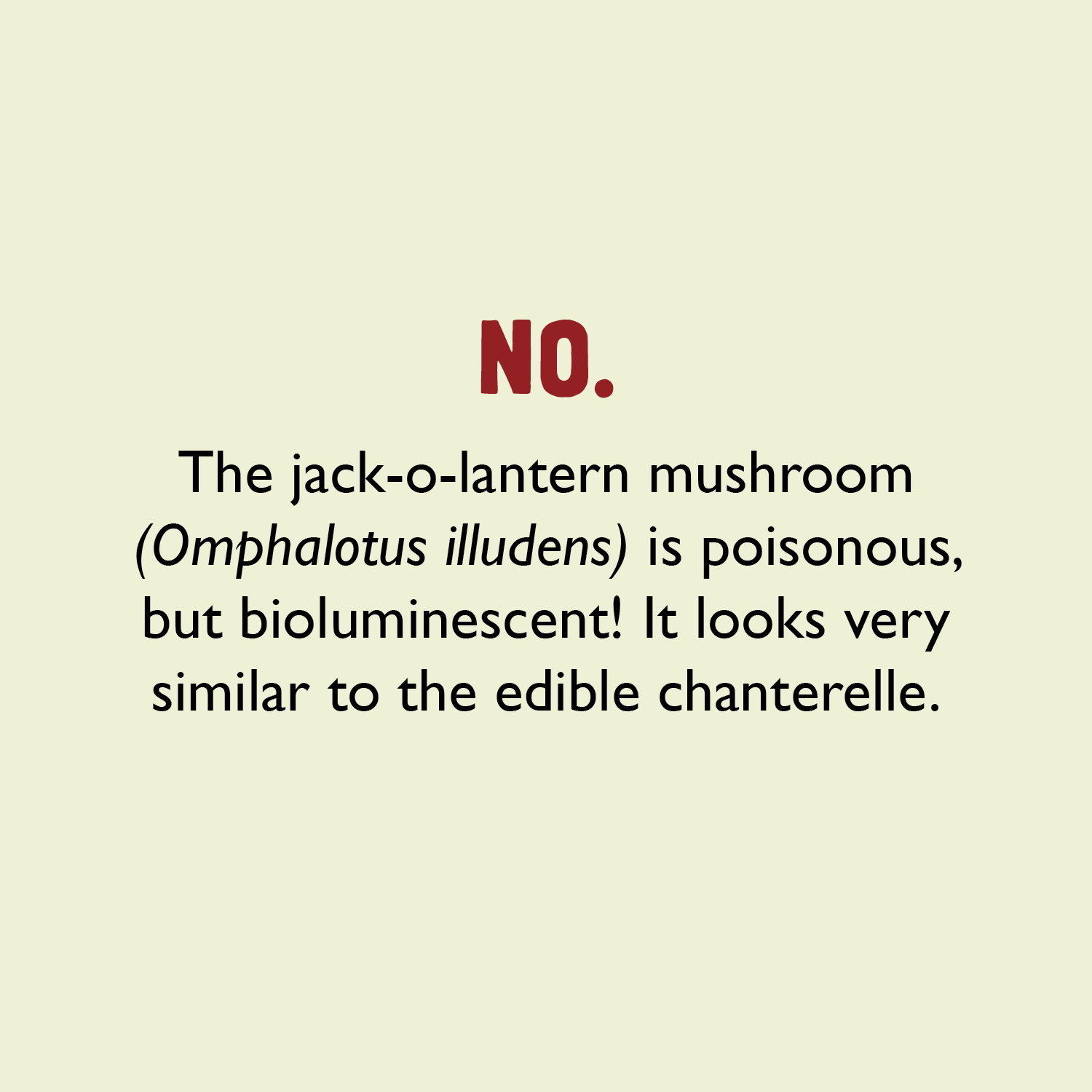

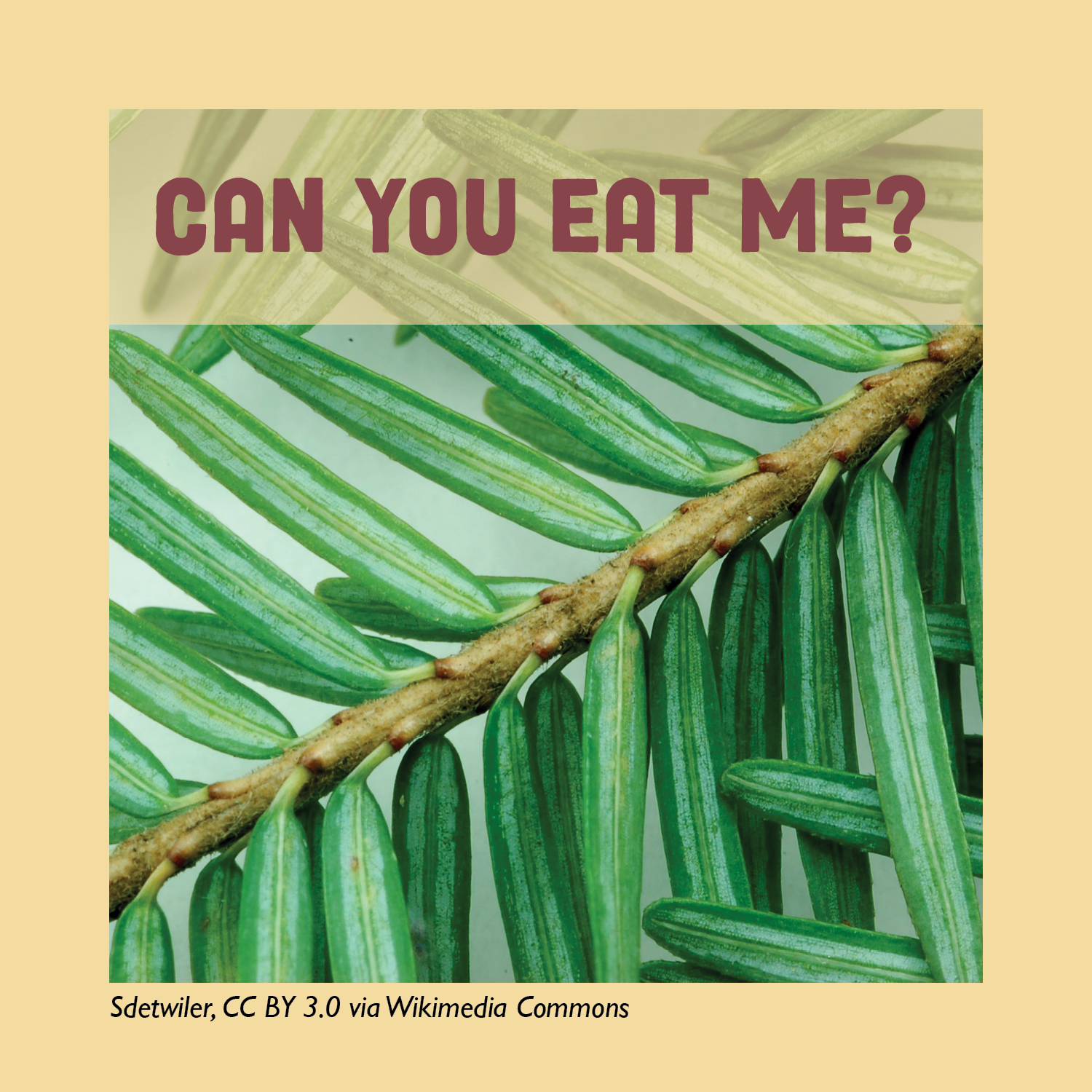

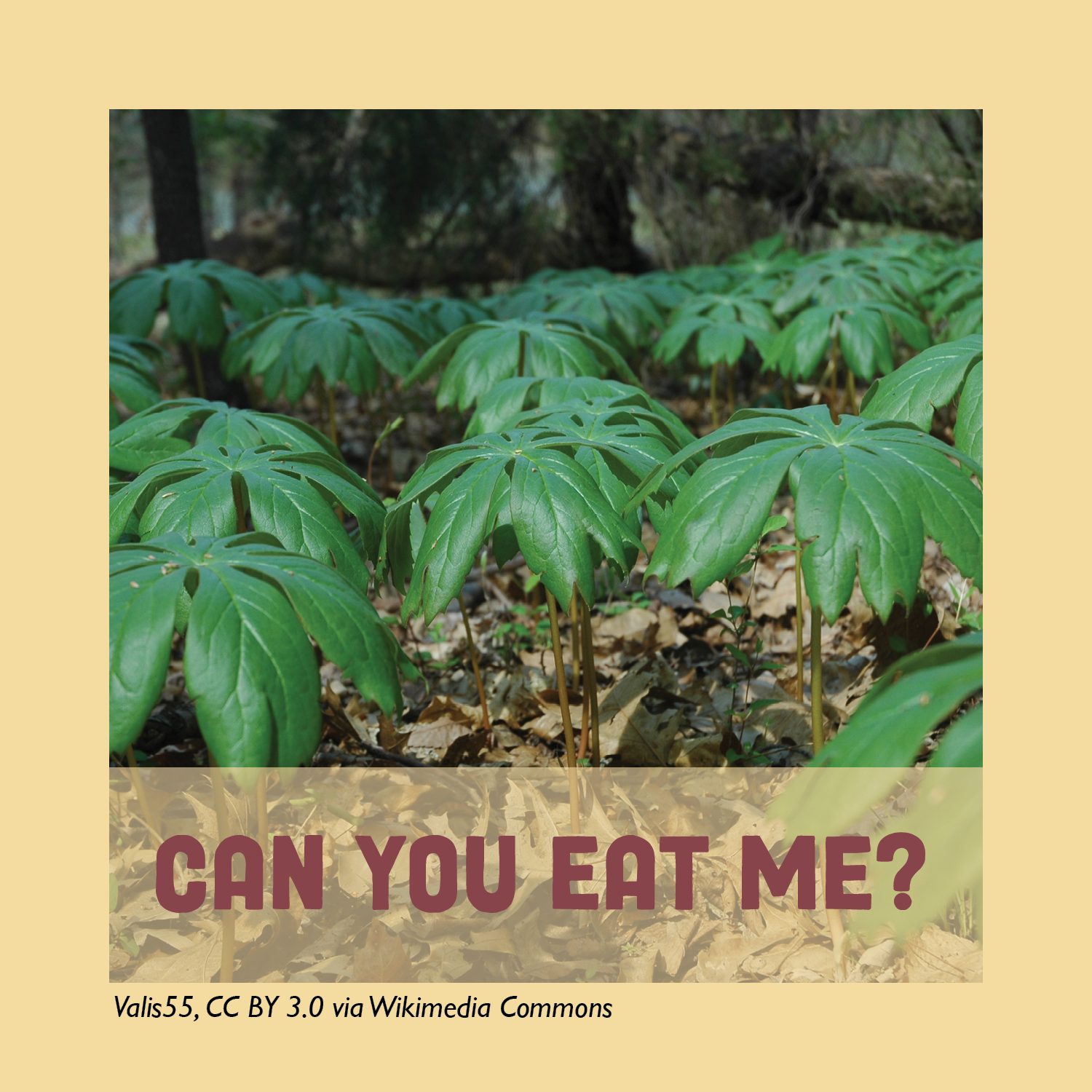

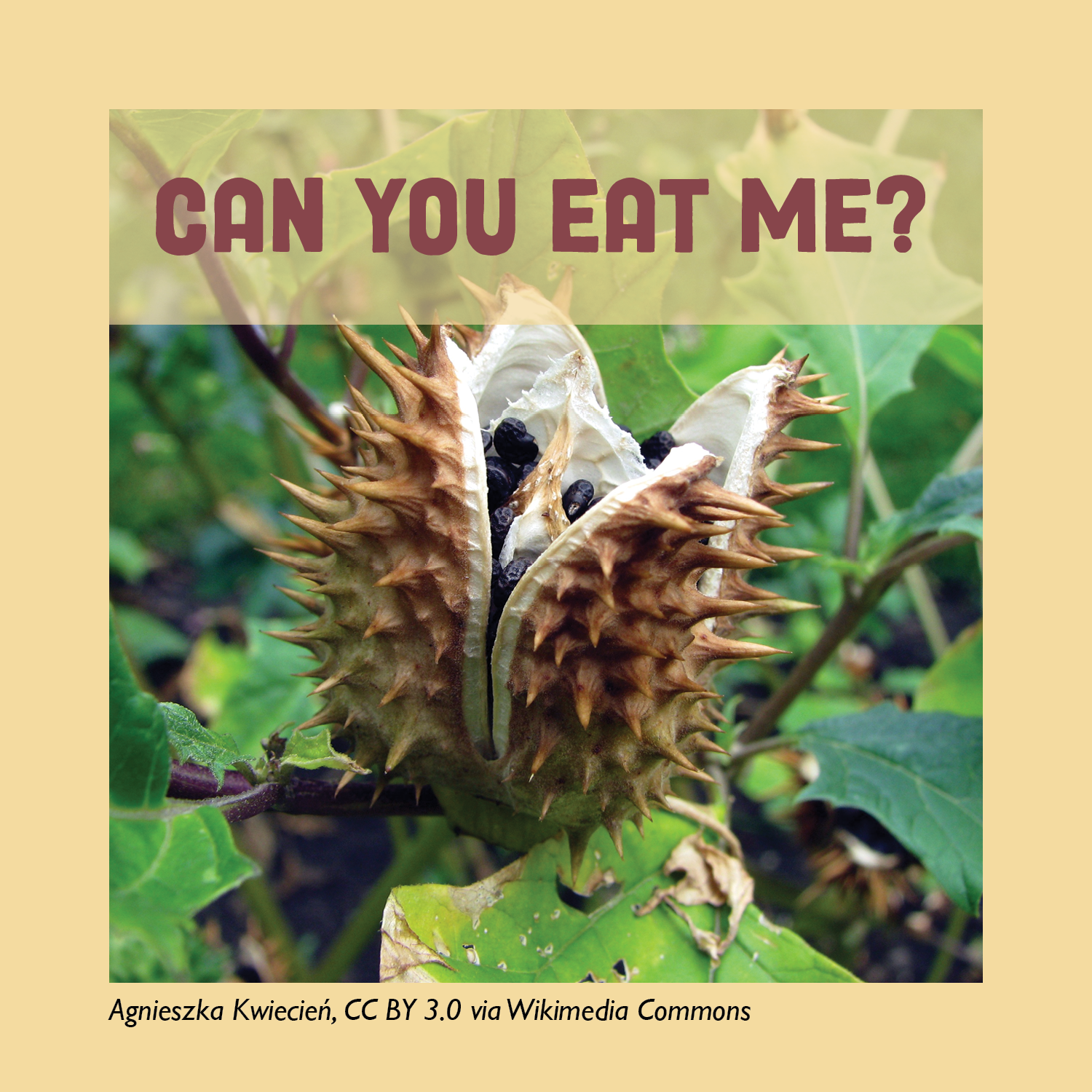

The summer months are a great time for foraging. Click through the slides below and see if you can tell the poisonous plants from the edible ones!

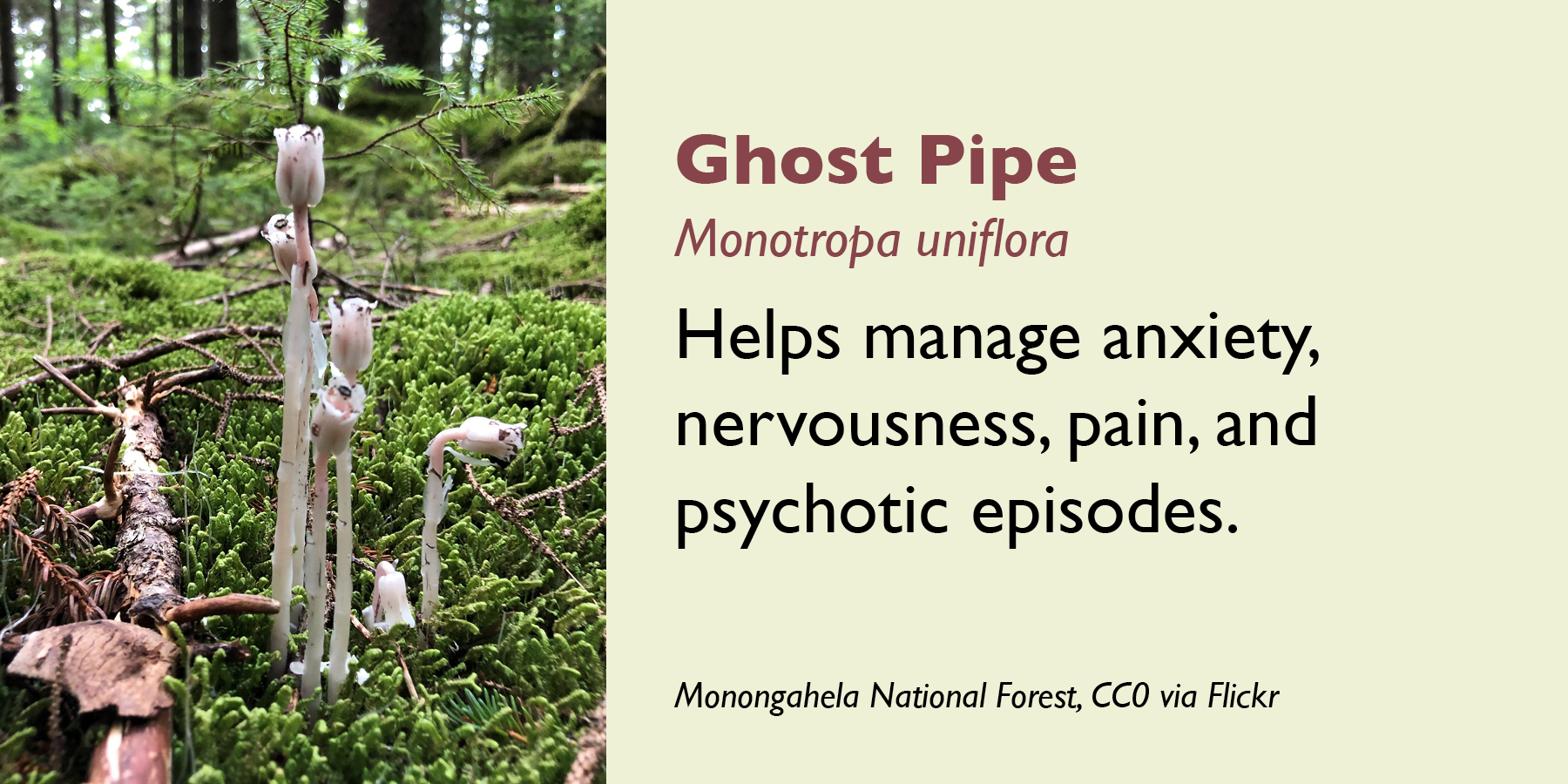

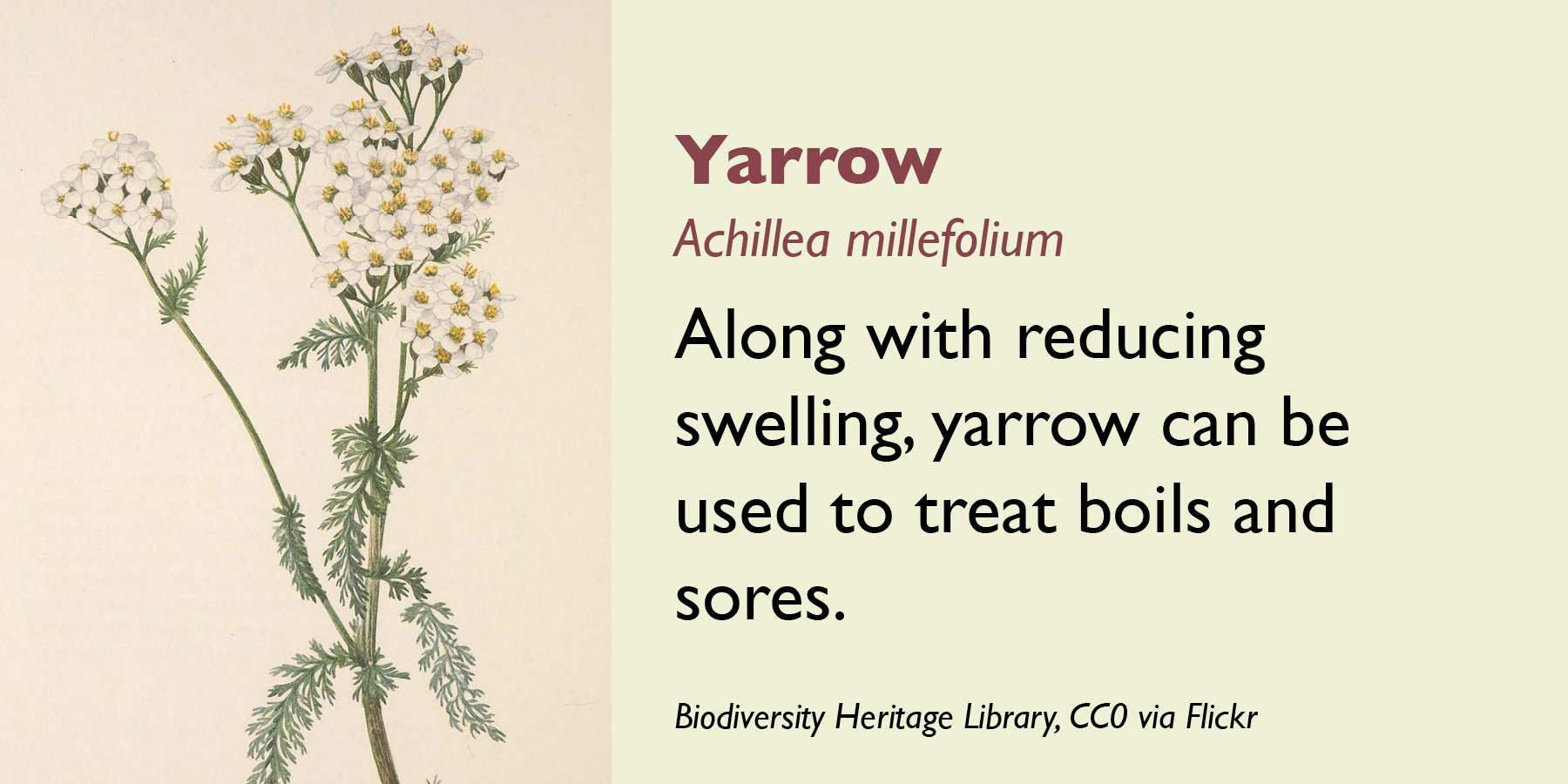

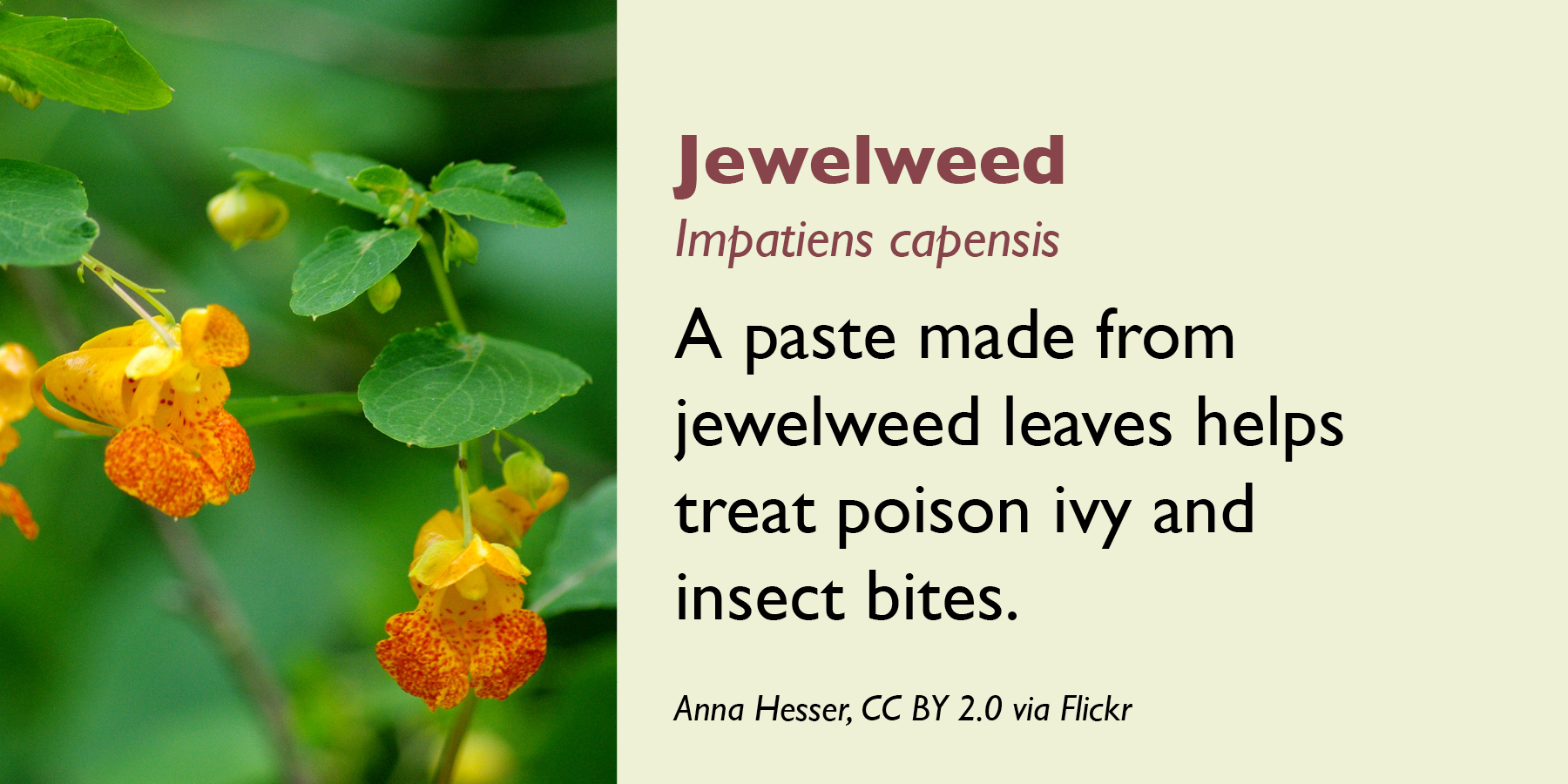

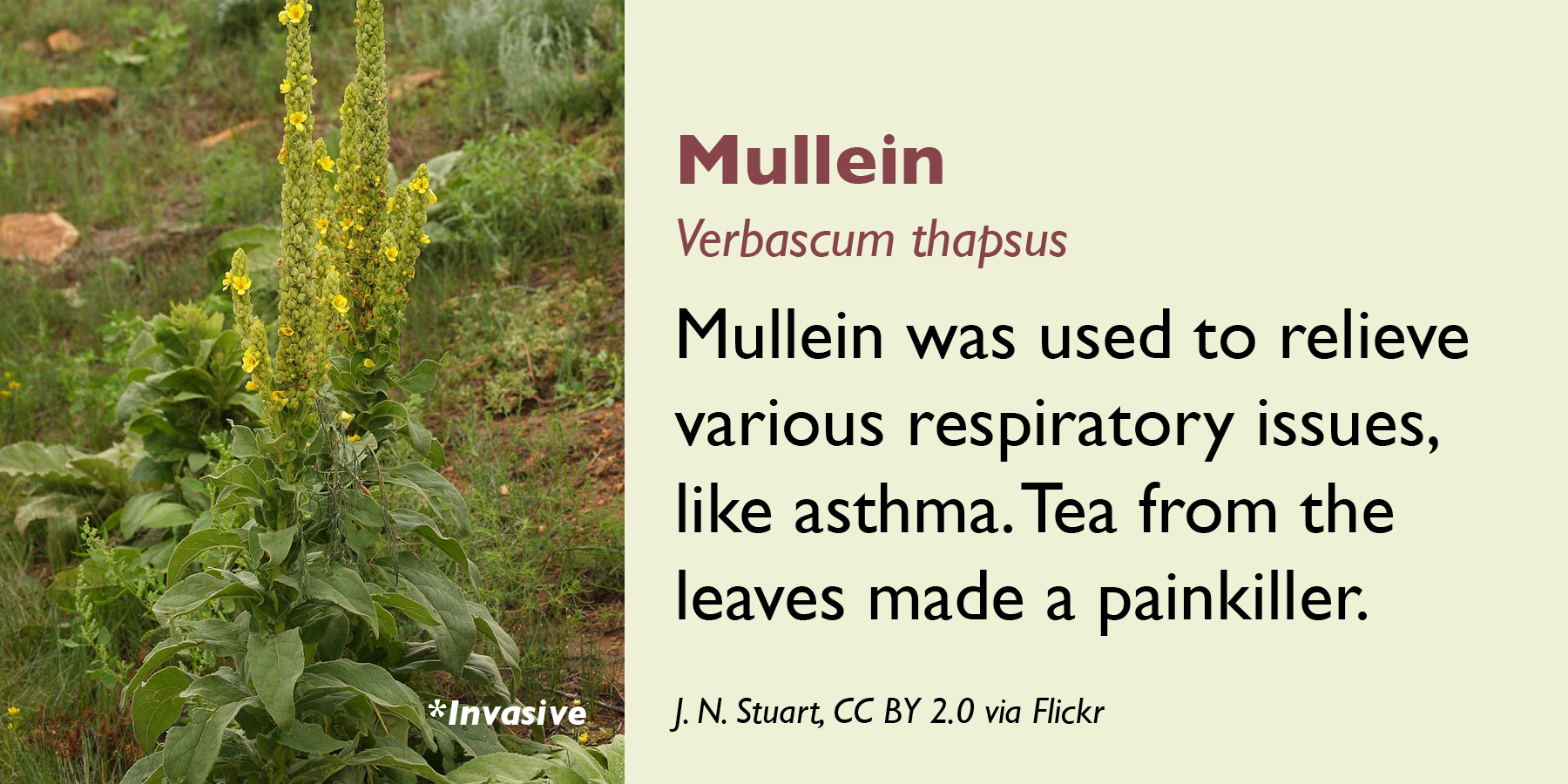

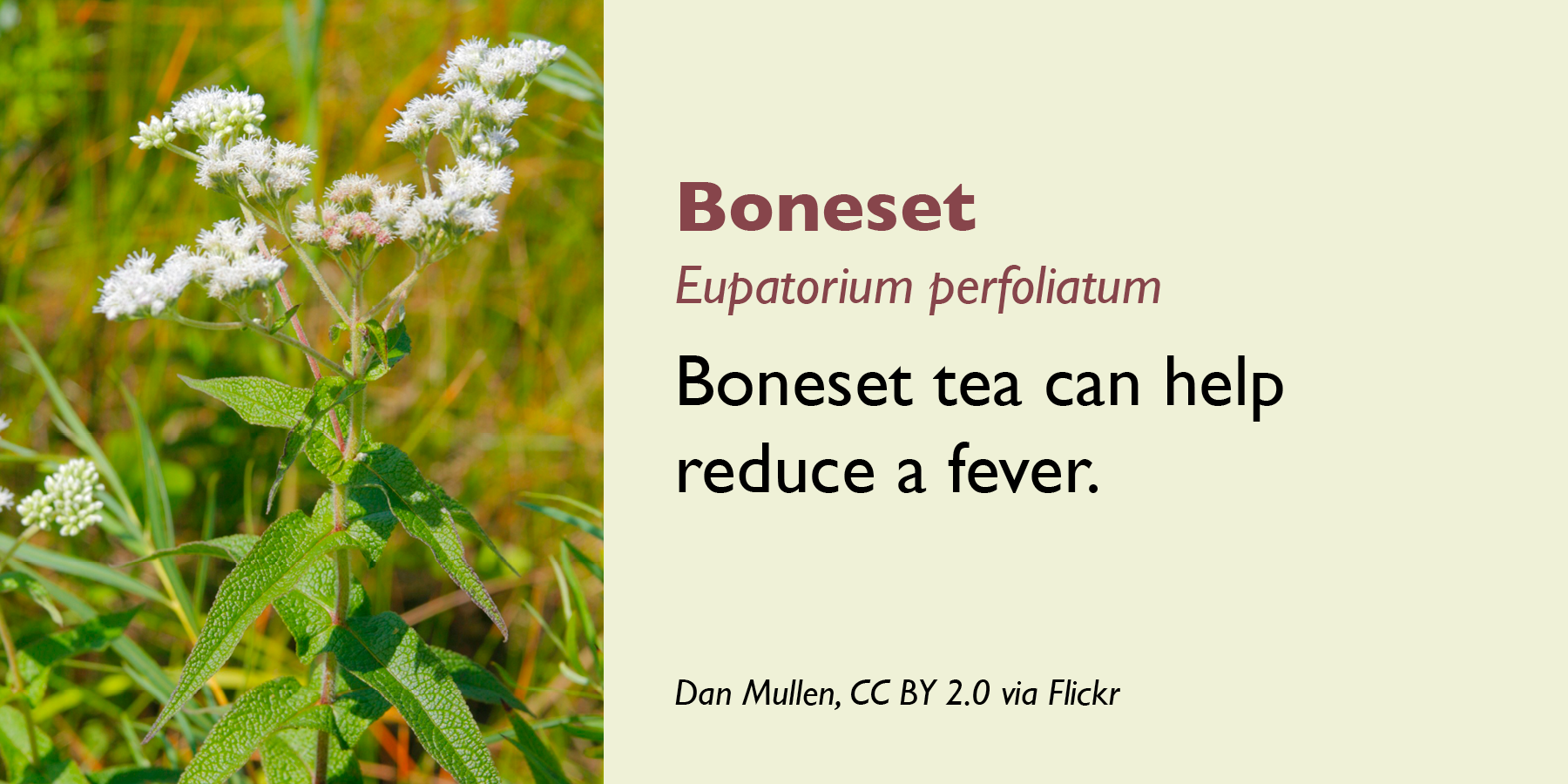

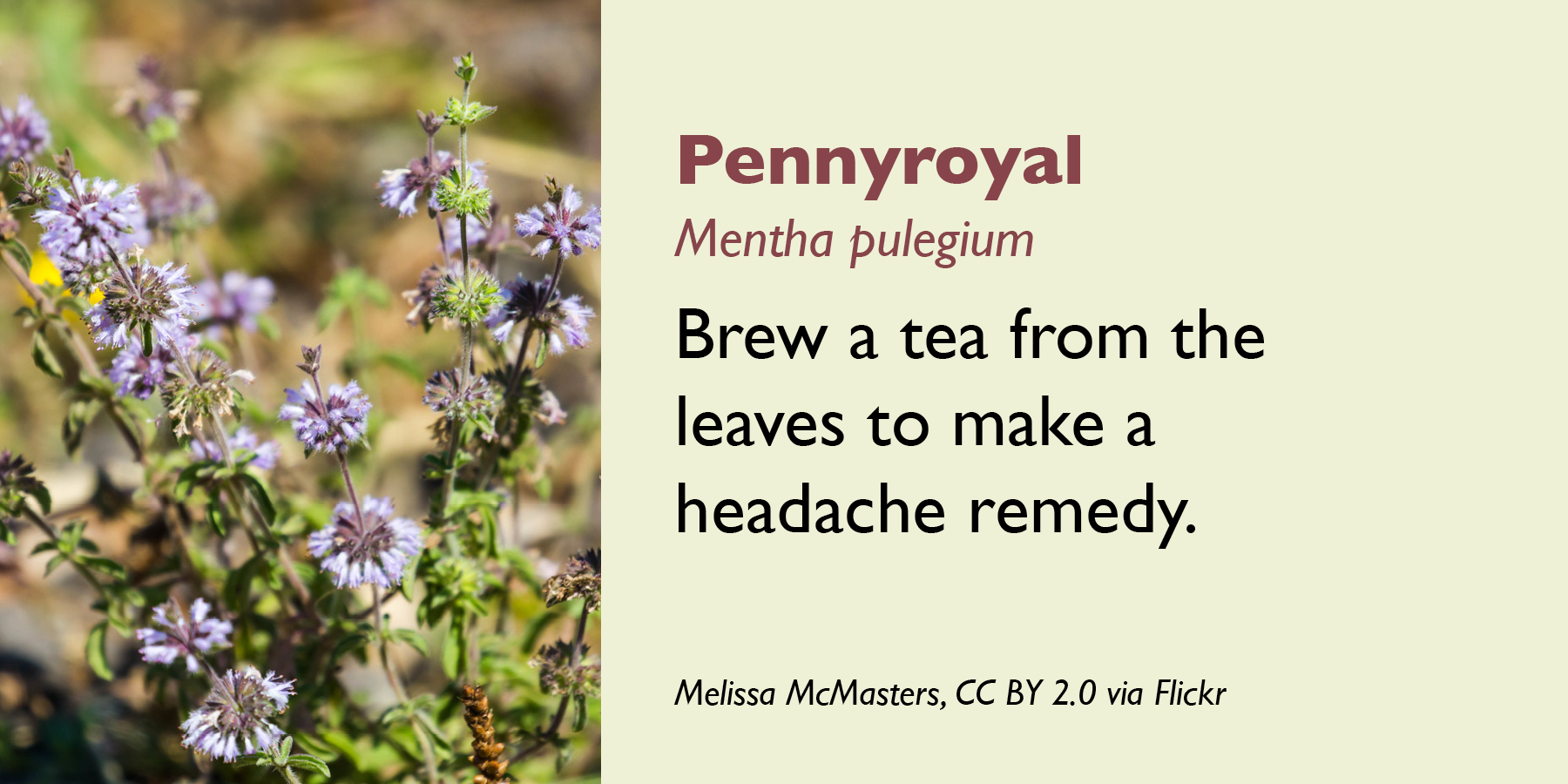

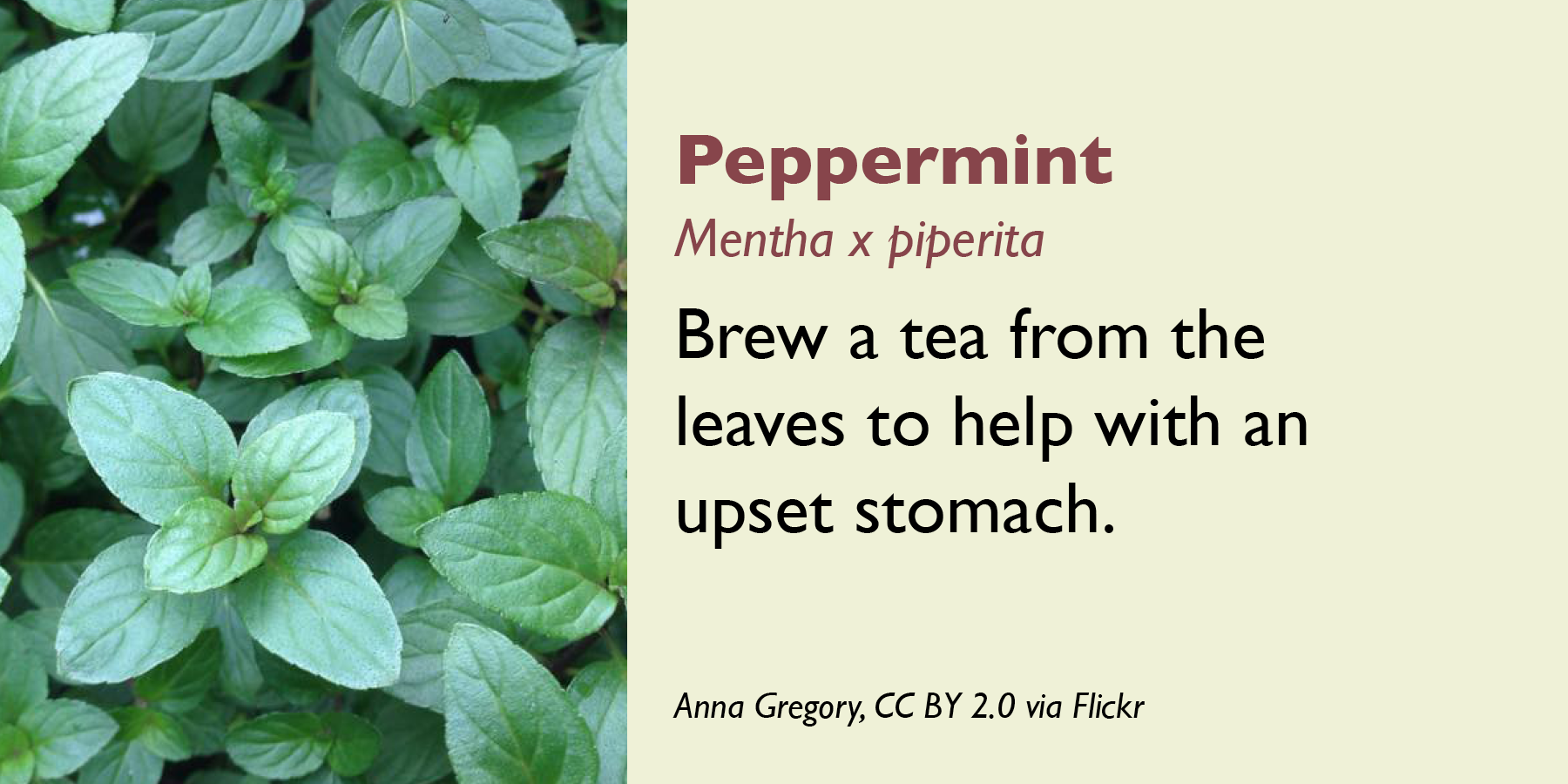

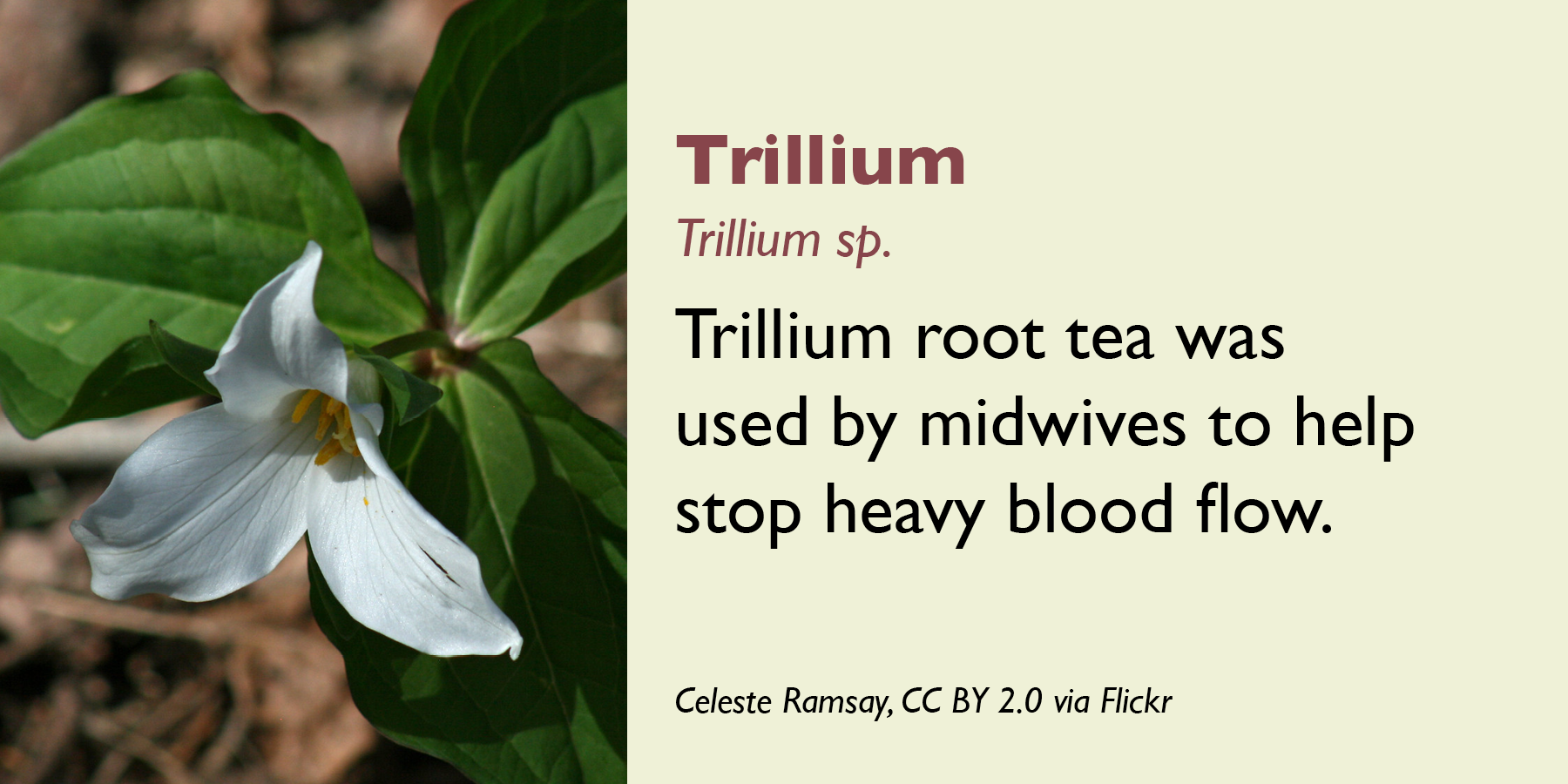

Hundreds of medicinal herbs can be found in the Appalachians. Remedies that required a plant’s leaves could only be accessed in the summer unless the plant was dried. Depending on what part of the plant is used and how it’s prepared, one plant usually has multiple uses itself. The plants presented here represent just a handful of those used by people in this area. Across Indigenous, African, and European botanical traditions, many plants were used similarly, while others had cultural significance or practical uses unique to individual communities and their needs. Click through the slides below to learn some of the common medicinal plants used in the Appalachians.

Autumn

American Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius)

Image courtesy of the West Virginia Folklife Program Collection

Highly sought-after and highly valuable, ginseng has always been a resource for Appalachians in times of need. American ginseng has held economic value in the United States since the mid 1700s, though it was used medicinally by many Indigenous peoples prior to that. The highest demand for ginseng comes from China and Korea, where the root has been used for thousands of years in traditional medicine. In Appalachia, selling ginseng roots has provided people with a way to make extra income, both historically and today. For many though, hunting ginseng is also just a fun way to spend time with friends and family. Ginseng’s harvest and export are now tightly regulated, as habitat destruction and over-harvesting have put it at risk.

Pawpaw fruit (Asimina triloba)

Image courtesy of Anna Hesser, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The edible fruit of the pawpaw tree was popular among early Appalachians. Pawpaws are the biggest fruit native to North America. For Native American nations like the Shawnee, the pawpaw is a tie to their ancestral lands in Appalachia (read more here: Searching for the Pawpaw's Indigenous Roots) Other tree fruit, like persimmons, are also popular to harvest in the fall.

Tree nuts, like acorns, black walnuts, American chestnuts, hazelnuts, and hickory nuts were also collected, processed, dried and eaten— ground into flour or added to baked goods.

Winter

One way to tap a tree is to insert a small tube called a spile into a hole or notch cut into the trunk. The sap flows from the tree through the spile and collects in a bucket. Above, a full bucket of sap is being emptied into a collection bucket.

Image courtesy of the USDA Forest Service

Sugar Season On the first warm days of late winter, the sap of the sugar maple begins to run and can be collected. Maple sugar was an important part of the diet for the Huadenosaunee (the Iroquois Confederacy) and Shawnee. From February to May—maple season—families would move to the sugar bush to collect sap. The sap could be drunk fresh, fermented, or boiled down into maple sugar. The Seneca would mix maple sugar with cornmeal for a high-energy travel food, dissolve it into a drink, or use it to season meat. On hunting trips, it was mixed with bear grease in a bear gut bag and meat was dipped into the bag.

When settlers arrived, Native Americans taught them how to make maple syrup and sugar. Records from Ely Butcher’s country store here in Randolph county show that maple syrup was a popular item to barter. It was a good subsitute for cane sugar, which was harder to come by. Maple syrup making remains a tradition in West Virginia, celebrated annually with festivals across the state.

Weaving with Wood Appalachia is rich with basket making traditions. A necessity for daily life, baskets were made to be practical. Much skill and consideration goes into making well-structured baskets, which were needed for everything from gardening to laundry to going to market. Baskets can be woven from many different materials—white oak is very common in this area, and black ash is used traditionally among the Northeastern Woodland Indigenous peoples, like the Seneca Nation. Like selling medicinal roots or maple sugar, basketmaking was also a way for people to make extra income.

The winter months were also a good time to harvest tree bark for medicine. Click through the slides below to learn more.

Conservation

Appalachia is home to some of the most biodiverse temperate forests in the world. Unique habitats are found across the Appalachian mountains, host to some plants and animals that are only found in Appalachia. This includes valuable plants and fungi. However, habitat destruction and overharvesting have put many of them at risk. Like dominoes, the disappearance of a few species can set into motion a complex chain of events, impacting the stability of forest ecosystems, human health, and the future of cultural traditions centered around those species. Click through the slides below to learn more about these connections.

For more on at-risk medicinal plants in Appalachia, check out the United Plant Savers’ Species At-Risk List.

further reading

A Field Guide to Appalachian Medicinal Plants (US Forest Service)

Homegrown Foodways in West Virginia, a series of films on food traditions in the state